In light of concerns over political interference, many countries halted their cooperation with China’s Confucius Institutes, allowing Taiwan’s Mandarin learning centers to grow. However, the organization’s decentralized nature has led to a different path of development.

Key takeaways:

-

In response to global concerns about the Confucius Institutes, Taiwan launched its own Mandarin education initiative in 2021 to strengthen its soft power under democratic values.

-

The Taiwan Center for Mandarin Learning (TCML) operates as a network of independent institutes across various countries, which differs from Confucius Institutes in the extent of centralization.

-

To deepen its impact, Taiwan should provide stronger institutional support and develop more cohesive strategies for expanding its Mandarin education programs globally.

Is Mandarin becoming the battleground for soft power between China and Taiwan? This article compares the development of China’s Confucius Institutes (CIs) and Taiwan’s Center for Mandarin Learning in four Central European countries (the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia). As Taiwan grows its informal ties with the region, Mandarin education in these countries is one of the areas to follow.

Overview: current debates on Mandarin education institutes

Over the years, global demand for Mandarin education has surged. Riding this wave, CIs, China’s official educational outreach brand, underwent rapid expansion in the latter half of the 2010s, establishing itself as a key vehicle for Chinese cultural diplomacy. By the end of 2023, the number of CI branches worldwide had reached 548.

Operating through partnerships with local institutions, CIs were integrated into national education systems, a model that facilitated their rapid global expansion. Initially, they were overseen by the Hanban—officially known as the Center for Language Education and Cooperation (or Hanban), a body directly under China’s Ministry of Education. In 2020, governance of the program shifted to the Chinese International Education Foundation, a state-affiliated NGO jointly organized by 26 Chinese universities and institutions, including Peking University, Fudan University, and the Palace Museum in Beijing.

However, in recent years, concerns have mounted in the United States, Europe and other like-minded countries about CI’s role as a conduit for political influence. Under President Xi Jinping’s leadership, Beijing has increasingly leveraged these institutes for ideological promotion, prompting growing unease about their integration into foreign educational systems. In many cases, this scrutiny has led to restrictions on CI operations or outright closures.

In 2020, the European Parliament passed a resolution addressing foreign interference within the EU. It flagged the CIs as instruments of the Chinese Communist Party’s political messaging and economic ambitions. The resolution urged member states to protect their sovereignty by revoking CI licenses or withdrawing funding and instead promote independent Chinese language programs free from Chinese government involvement.

Across the Atlantic, the United States took similar action. In September 2024, Congress passed legislation barring the Department of Homeland Security from funding educational institutions that collaborate with CIs or other “Chinese entities of concern.”

The result has been a sharp decline in CI presence across both Europe and the United States. The Free University of Brussels closed its CI in 2019 following espionage allegations against its director, while Sweden shuttered its last remaining CI in 2020 amid worsening relations with China during the pandemic. According to a report by the US Government Accountability Office, the number of CIs in the United States plummeted from around 100 in 2019 to fewer than five by 2023.

In response, many universities have turned to alternative sources for Mandarin instruction, relying on in-house academic departments or forging partnerships with Taiwanese organizations. Sensing an opportunity, Taiwan launched the Taiwan Center for Mandarin Learning (TCML) in 2021. Marketed as a democratic and open alternative, TCML promotes academic freedom while offering Chinese language education untainted by geopolitical baggage.

Confucius Institute in Central Europe

In Central Europe, 14 CIs are currently in operation, with the first opening in Krakow and Budapest in 2006. Many more Confucius Classrooms operate across the region. The presence of CISs often reflects the broader political relationship between China and the host country. Hungary, under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, has actively positioned China as a strategic partner and now hosts six CIs, making it a regional hub for Chinese cultural outreach. At Eötvös Loránd University alone, more than 25,000 students have enrolled since its CI was established.

By contrast, the Czech Republic and Poland have adopted a more cautious stance. Although similar in size to Hungary, Czechia hosts only two CIs. Efforts to expand CI presence have been met with institutional resistance: several universities declined to host new branches, and in 2023, Palacký University in Olomouc ended formal cooperation with its CI, which subsequently restructured into an independent entity outside the university system. Enrolment figures also reflect this reluctance—only 306 students attended classes at the CI housed at Prague’s University of Finance and Administration (VŠFS) in 2023. In Poland, the Wroclaw University and Warsaw University of Technology, which previously hosted Confucius Institutes, did not extend the inter-university cooperation contract for their functioning.

TCML: a decentralized organization for Mandarin education

Amid growing skepticism toward CIs, many Western countries have begun seeking alternative avenues for Mandarin education outside of China-sponsored institutions. In response, Taiwan launched its own language-learning initiative in 2021: the Taiwan Center for Mandarin Learning (TCML). Established by the Overseas Community Affairs Council, TCML was initially part of the Taiwan-US Education Initiative and focuses on promoting Mandarin instruction primarily in North America and Europe.

The program’s core aim is to broaden access to Mandarin education while preserving academic independence and intellectual freedom. As of now, TCML operates 84 centers across 14 countries, including 21 in Europe. It presents itself as a democratic, open, and politically neutral alternative, emphasizing a learning environment free from censorship or ideological influence.

The TCML program has largely grown through partnerships with existing overseas compatriot schools and community associations experienced in Mandarin instruction. As of 2024, three TCML centers operate in Central Europe, each with a distinct development trajectory.

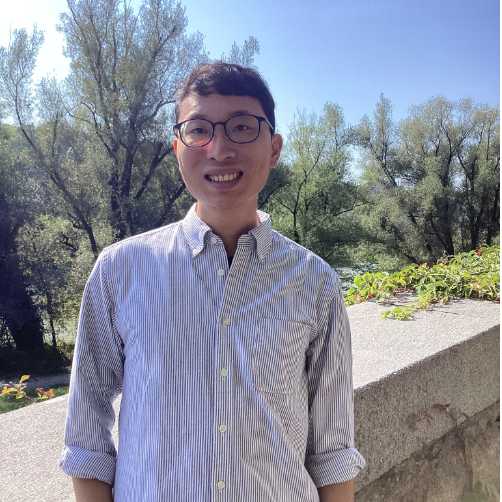

In Hungary, the TCML is run by the Jade Mountain School, a private language institute founded in 2019 by Yi-Ying Lee, a Taiwanese teacher based in Budapest. After several years of independent operation, the school was formally recognized by the Overseas Community Affairs Council (OCAC) in 2022 and became an official TCML partner.

In the Czech Republic, the TCML is managed by the Czech Taiwanese Association, a community organization that fosters ties among Taiwanese residents. With support from the Taipei Representative Office in Prague, the association established a Mandarin learning center in 2019, receiving OCAC funding from 2023. Unlike the Jade Mountain School, the Czech center began with a mission to educate children of the Taiwanese diaspora. As Czech-Taiwan relations have deepened, the association has expanded its programming to include courses for local Czech students. In line with Taiwan’s Mandarin Education Enhancement Program, it has also built partnerships with Czech public schools to offer in-school instruction.

Though both the CI and TCML serve as instruments of soft power, they represent fundamentally different models. TCML functions as a decentralized network rooted in civil society and shaped by grassroots partnerships with the Taiwanese government. As the Hungarian and Czech cases show, each center evolves along its own path: one emerging from an individual entrepreneurial effort, the other from a broader community initiative. The Czech association, in particular, plays a dual role—serving both overseas compatriots and foreign students, reflecting a hybrid educational mission.

While CI and TCML differ in scale, Taiwan does not appear to be pursuing parity in numbers—TCML positions itself not as a rival, but as an alternative. Rather than compete on size, it leverages Taiwan’s core strengths: academic freedom, openness, and pluralism. In doing so, TCML offers not just language instruction but a distinct educational philosophy—one that sharply contrasts with the centralized, state-driven model of the CIs.

What’s next for Taiwan’s Mandarin education?

Interest in Taiwan’s approach to Mandarin education is rising, particularly in Europe and the United States. In 2023, a record 36,350 international students traveled to Taiwan to study Mandarin, reflecting the growing global appetite for a politically neutral and academically open alternative to China-sponsored programs.

Building on this momentum, Taiwan is well-positioned to further capitalize on its unique strengths in Mandarin education. One potential path forward is expanding collaboration between TCML centers abroad and established language institutions in Taiwan—particularly in areas such as teacher training, curriculum development, and faculty exchange. Such partnerships could help TCMLs scale beyond their current community-based model and offer more comprehensive services.

The recently launched 2025 Mandarin Education Enhancement Program represents a significant step in this direction. Aimed at strengthening Taiwan’s soft power through education, the initiative introduces a suite of reforms designed to better integrate resources and elevate the quality of instruction. Among the key measures are standardized criteria for teacher qualifications, updated assessment tools for students, and a more unified approach to curriculum and testing. These developments are expected to enhance learning outcomes and solidify Taiwan’s role as a credible and values-driven leader in global Mandarin education.