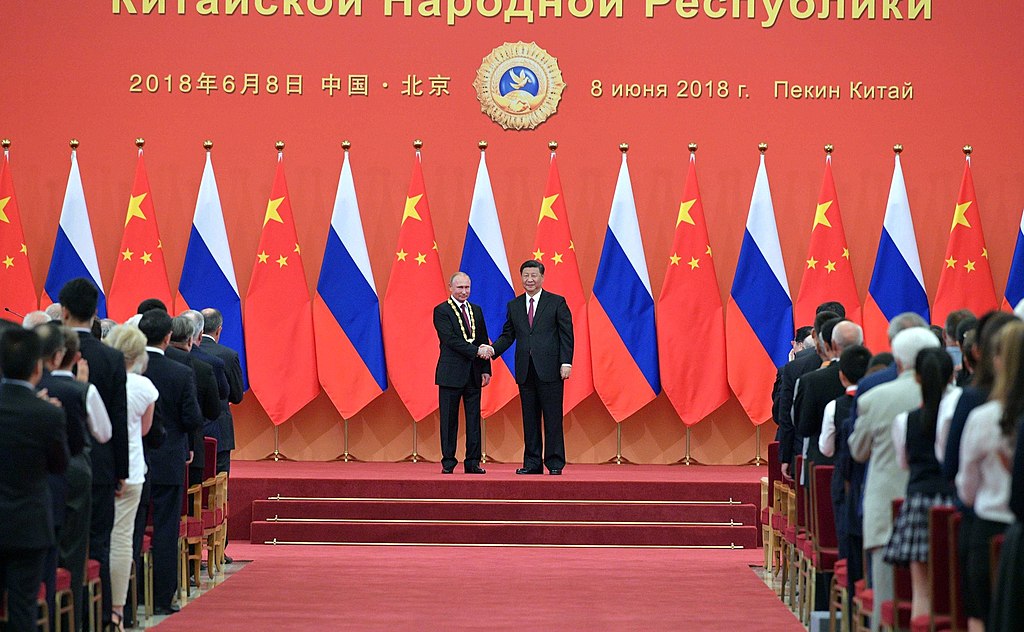

Russia and China have been maintaining both political and economic ties for years. Most people around the world have heard or read about that close partnership and even friendship between the two countries. However, it is just a view from the outside, so it does not reflect the very Russian perspective. That is why we present in this article an insiders’ analysis of Russian optimism and anxiety about cooperation with China, in particular regional cooperation within BRICS.

Several Russian foreign policy think tanks recently discussed Russia’s “drift to the East”. This article focuses on the analysis of such discussion and particularly the assessment of Russian experts of China’s role in BRICS, the cooperation format between Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Many Russian scholars believe that due to its financial might China plays a key role in BRICS. To explain the diversity of contemporary narratives of China in Russian political discourse we have examined 26 articles published by some of the most recognized Russian foreign policy think tanks.[1]

Common features in the Russian discourse on China

Our analysis aimed to structure the textual data to reveal patterns reflecting the experts’ opinions about China’s role in BRICS. In other words, we explored so-called discursive frames depicting regional cooperation structures. Overall, as a result of the narrative analysis we have detected seven common features widely seen in the articles of the abovementioned experts:

- The global order has been altered, in particular the role of global economic governance. The shift is caused by a change in developing countries’ statuses. They are increasing their economic performances as well as political presence;

- Traditional Western international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank do not take into account the developing countries’ status, which has been adjusted significantly;

- We should note that we are talking here about the status of Russia and China as developing countries. China’s role in the world has transformed dramatically since the early 2000s. It has gained economic power and started expanding it around the world. In comparison with China, Russia tried to change its political course at least from 2007. Moscow has chosen its foreign policy as containment of the West; thus, it has been contesting its status-quo in world politics. Chinese and Russian growing influence (economic and political respectively) meets as much optimism as fear and criticism from other states. There is still room for debate on how to interpret this situation. However, the key point here is that everyone pays attention to the evolution of the statuses of these two developing countries.

- Western hegemony is being replaced by polycentrism;

- The present-day international situation is a promising opportunity for BRICS. The current global governance and world order are lacking the balance between various new actors. Therefore, close cooperation within BRICS is becoming a chance to reach such a balance.

- BRICS has chances to be considered a “new center of power”;

- National currencies of the BRICS members could become a substitute for the US dollar within BRICS or even globally;

- BRICS has perspectives to provide controlled globalization and cross-regional integration processes.

Overall, our research showed that, according to a majority of the Russian experts, BRICS is assigned the role of a new responsible stakeholder in the international arena. However, more profound analyses raise new questions: since BRICS, above all, is a group of independent nation-states, does that consequently mean that their influence within BRICS is distributed so unevenly that it becomes an obstacle for a consistent common political and economic agenda? Does BRICS have the capacity to make any changes within the current international order? What is the unique agenda promoted by BRICS, and does the organization have a plan of common action?

An in-depth analysis of the abovementioned questions has shown that the Russian experts do not have a homogeneous opinion on Russian-Chinese cooperation within BRICS. We have identified those differences along the axis marked by us with two opposites: first, the inspiration of Russian experts by the bilateral interaction within BRICS, and, second, anxiety about China’s growing influence within BRICS.

The inspiration: Russia’s optimistic view of China

The inspirational segment of Russian political discourse represents the role and perspectives of China in BRICS in an optimistic way. Within this pool of articles, we have distinguished the following inspirational narratives and sub-narratives:

- China advocates enhancing the role of the developing (low and middle income) countries on the international scene. Beijing’s goal is to promote multilateral world order.

- China attaches great importance to the political and economic interaction within BRICS, especially ties with Russia.

BEAMS is China’s “circle of friends”:

- China offers the BEAMS[2]/BRICS+ format that implies inclusive win-win cooperation, which is primarily oriented toward “South-South” – a community of worldwide developing countries.

- It is suggested that BRICS would become an “aggregative platform” for comprehensive cooperation between developing countries on several continents.

- China considers and Russia supports BEAMS/BRICS+ as a basis for a new global economic architecture.

Global integration between developing countries is a priority:

- China proposes regional and cross-regional economic integration against increasing Western protectionism.

- China pursues the harmonization of the global order and international relations; Beijing is highly interested in BRICS as a platform for dialogue.

China is a key partner for Russia both globally and regionally:

- China is the Eurasian Economic Union’s (EAEU) major trade and investment partner

- Officially Beijing fully supports integration processes in the EAEU.

- The Sino-Russian partnership is mutually beneficial cooperation, it has become a stabilizing factor and a “point of reference” in the complicated and constantly changing international environment.

China is still considered to be a developing country. However, economically speaking, it is a key world player along with the United States. According to experts from the inspirational group, Beijing did not have enough political capacity some time ago, however, the situation is changing. China is seeking to alter the global order, especially the system of economic governance created by the Western states. Beijing’s main option to do so is to encourage other developing countries to forge a common (decolonizing) front. It looks like an attractive initiative for everyone: developing countries could get Chinese investments along with opportunities for their domestic growth. On the other hand, China simultaneously could get a chance to promote its role as a challenger of the current international order and Western hegemony.

In addition to “Beijing’s common front”, we can witness the creation of countervailing power to the American protectionism, which is specified by China’s idea of promoting inclusiveness through integration. Such initiatives as the Belt and Road Initiative or BEAMS+, from one side, provide real chances for developing countries around the globe to mitigate their economic underdevelopment. On the other side, both BRI and BEAMS+ strengthen China’s mechanisms of enhancing its influence to confront its main political rival – the United States.

Bilateral relations between Russia and China are closely related to Eurasian cooperation taken widely. Such cooperation brings increasingly closed interaction within BRICS, SCO, EAEU, and BRI. In the case of the inspirational frame, Russian experts claim the primacy of China as a partner in the region. Hence, Moscow has opportunities to promote its national interest with Beijing’s support in the international arena and vice versa. As we know Russia has been tending to confront the West, especially the U.S., at least since 2014, so it indeed needs to maintain strong political ties with the Asian member of the United Nations Security Council.

Russian anxieties

Speaking of Russian anxieties about China, narratives and sub-narratives seem to appeal to Russia’s national security as follows:

BRICS is not an effective institution:

- The BRICS members are utterly different countries. Thus, they would not be able to develop a common comprehensive strategy, neither can they become a united power center with capabilities to influence the world order.

- It is rather unlikely that BRICS will become an alternative power in the international society, while Western countries’ hegemony is likely to be preserved.

Currently, China has greater political, economic weight within the international society than other BRICS members:

- unlike Russia, China has started to feel self-confidence and strength as a new world leader, and “does not suffer from an inferiority complex”.

- Russia produces less than 8% of the BRICS’s GDP, while China produces 65%. We cannot talk about any equality and mutually beneficial cooperation under such a financial disparity.

- Beijing expects to use BRICS to modify the world financial system, to make it more convenient for itself.

- China might look at BRICS as a testing bridgehead for new ideas that will be selectively implemented in other projects.

- By working on the BRICS Bank and the currency pool China will gain invaluable practical experience in implementing development projects, playing the role of a leader rather than a subsidiary.

China does not need any “friends”, thus it will not take Russia’s side:

- Sino-Russian cooperation is not based on equality. China uses it to accomplish its own goals, but not to support Russia in its confrontation with the West.

- Russia’s dependence on China is increasing, thus it might become a Chinese “younger brother”.

- Russia remains in the “euphoria of China”, while China is more oriented toward economic cooperation with the US.

Those were the key anxieties of Russian experts about China’s role in BRICS. Their idea is that Moscow should be careful when dealing with Beijing. The latter has more economic power, so it may become a threat for Russia to get dependent on it.

China and Russia’s ontological insecurity

Russia’s narratives of China and BRICS also serve goals of what is called in contemporary International Relations Russia’s not just physical, but also ontological security. The latter is defined as narratives and the sense of continuity and order in international events with respect to a state’s self-identity. Our argument suggests that if the modern ‘Russian self’ maintains its sense of ontological security through conflictual relationships with the West, then Russian relations with the East start to play a key role to help Russia escape the feeling of complete international isolation and sustain domestic legitimacy. Then China, as a ‘key player in BRICS’ and the closest neighbor of Russia, can help to cement a collective Russian understanding of ‘Russianness’ which emphasizes traditional values and norms, all of which, as some scholars suggest, is under pressure from the West.

The narratives of Russia’s inspiration with China serve to support the self-identity of the Russian state and its ontological security as a country which (despite the Western sanctions) does not remain lonely in the international arena. “Russia and China are brothers forever” claims this version of the narrative, granting Russia almost the role of the USSR with its former greatness and industrial success to be rediscovered from the past at least on the level of Russia’s national imagination with the help of cooperation with China and BRICS.

Contrary to that, speaking about the anxious mood and fearful representations and narratives of China among Russian experts, we could notice that many of them seem to appeal to Russia’s sense of ontological insecurity. For example, we observe fears that cooperation with China can result in diminishing the role Russia plays in the Eurasian region and world politics in general. As suggested by experts from the July 2019 issue of The Economist, the brotherhood between these two countries may truly exist, however, this partnership is much more beneficial for China than it is for Russia. Some argue that “what seemed a brilliant way for Mr. Putin to turn his back on the West and magnify Russia’s influence is looking like a trap”, because China will dominate almost every aspect of the two countries’ cooperation. Lastly, it should be noted that Russia’s ‘drift to the East’ and our assessment of how Russian experts view China’s role in BRICS should be supplemented by more systematic research on, for example, Russian-Indian and also Russian-Brazilian relations, since they both structurally have a strong influence on how Russia imagines its future role as one of the leaders among the countries of ‘Global South’.

[1] Analytical Center for the Government of the Russian Federation, Carnegie Moscow Center, Institute of Far Eastern Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IFES RAS), Russian Institute for Strategic Studies, Russian International Affairs Council, Valdai discussion club. We then have explored the personal narratives of China produced by the expert community of the think tanks, which include, among others, renowned scholars like Dmitry Burykh, Sergei Vasiliev, Alexandr Gabuev, Leonid Grigoryev, Igor Denisov, Raisa Epikhina, Igor Ivanov, Alexandr Isaev, Sergei Karataev, Vasily Kashin, Mikhail Korostikov, Andrey Kortunov, Kseniya Kuzmina, Yuriy Kulintsev, Sergei Luzyanin, Akexey Malashenko, Andrey Movchan, Vladimir Petrovsky, Ivan Timofeev, Mikhail Titarenko, Petr Topychkanov, Dmitry Trenin, Sergei Utkin, Sergei Uyanaev, and Ekaterina Sharova.

[2] (BIMSTEC [Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation], Eurasian Economic Union, African Union, Mercosur and Shanghai Cooperation Organization).