In an attempt to improve the transparency of the upcoming elections in Myanmar, the EU inadvertently poured oil on the flames of the local racial conflict.

Five years after they voted in their first free and fair elections in many decades, 37 million people in Myanmar will soon go to the polls again, including 5 million first-timers. Myanmar will hold general elections on 8 November 2020 for more than a thousand seats in its legislative bodies. These will be the second elections under the quasi-civilian rule (with the military still holding a very strong position) following the so-called transition (a very vague term that can refer to anything really) – a top-down decision that led in the 2010s to political changes (but not necessarily democracy as many expected or hoped for).

Tensions are high in the wake of the elections and the list of shortcomings is long. First of all, holding elections in times of a pandemic is no easy task for anyone. Since Myanmar’s first COVID-19 cases in March, there has been a surge in new infections with a total of more than 29 000 reported cases and 664 deaths. Nevertheless, election officials say the elections will take place as scheduled. This reminds one of the Nargis situation in 2008 when the deadly cyclone ripped through the country and effectively barred many people from physically making it to vote in the constitutional referendum (the current undemocratic constitution itself points to a major flaw in the upcoming elections), but the military leadership decided not to let that fact stop them from pushing on.

While the pandemic is unlikely to alter the overall election result – the ruling NLD will almost certainly sweep the ethnic Burman heartland (the country’s ethnically diverse periphery is more uncertain), it has significant implications for the electoral process and its credibility. Stay-at-home orders have been enforced in several regions and effectively banned many political parties from in-person campaigning. Also, many well-known media outlets had to stop selling newspapers (with their journalists not allowed to travel to election-related events or to produce physical copies of the papers) – (un)surprisingly, the two state-owned newspapers have been able to continue printing.

Moreover, because of the exceptional circumstances created by COVID-19 travel restrictions (international flight suspended at least until 31 October), there will be very scant international election monitoring. The Central Electoral Commission (UEC) approved over 8000 domestic observers and two international election observation bodies – the Carter Center and the Asian Network for Free Elections – as opposed to six such organizations, including the EU Electoral Observation Mission, in the last elections in 2015. International election observation is critical: Myanmar’s election process has flaws – it had flaws also in the previous elections, but people accepted the results, in part due to the presence of observers. If the ability to observe is impacted by COVID-19, that is likely to raise many questions.

Besides the pandemic hampering the election process, there is a long list of other systemic shortcomings, such as current voter lists being incomplete; military personnel in some areas allowed to vote inside military compounds; Internet access denied (for already more than a year) in conflict areas in Rakhine and Chin states; people in parts of Rakhine, Kachin, Karen, and Shan states not being able to vote due to armed conflict (constituency cancellations are made based on recommendations from the military); and one million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh and other countries, as well as the Rohingya remaining in Myanmar (about 600 000) not being allowed to vote due to the discriminatory nationality laws and practices.

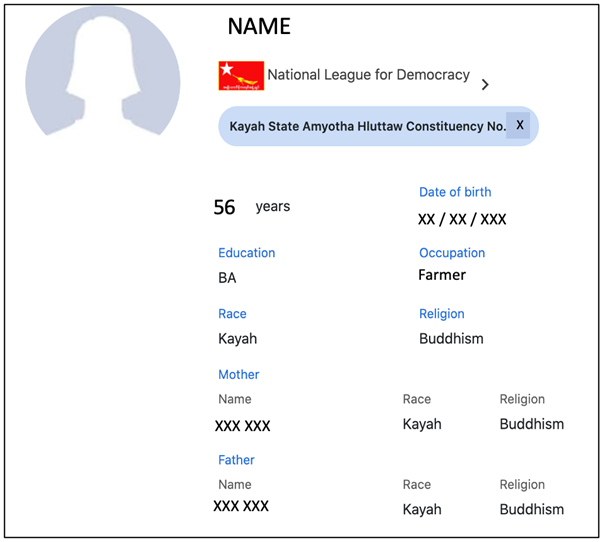

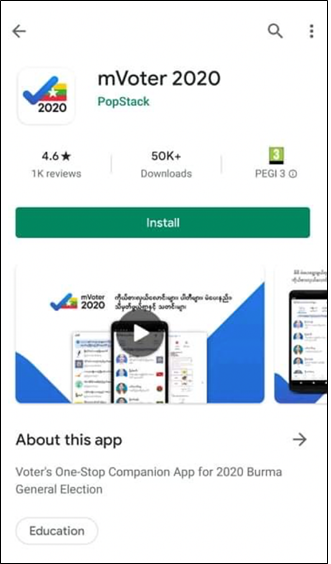

Unfortunately, the list does not stop here. Recently, to increase transparency, the EU’s official representation in the country initiated the creation of an app that would enable voters to meet the political candidates (also accessible through any web browser at https://web.mvoterapp.com/). The implementation was entrusted to Stockholm-based International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) operating in Myanmar, which filled the app with personal information about the candidates – without their knowledge – taken from the UEC. Shockingly, the mVoter 2020 app offers voters access to profiles of candidates that state each candidates’ and their parents’ (unnecessary) official “race” (meaning ethnicity) and “religion”. All this while the candidates featured in the app have no right to choose their “race” or “religion” and some are misrepresented.

Ethnic and religious identifiers do not aid in the democratization process in Myanmar and are considered sensitive in an ethnically and religiously volatile country such as Myanmar. The app explicitly directs voters to consider race and religion, when they should be considering candidates based on their political platform, regardless of cultural background or religious belief. Disclosing such information about the candidates thus risks inflaming ethnic and religious nationalism during the elections.

Moreover, the information contained in the app is complicit in erasing the Rohingya people’s identity. The Rohingya ethnic group, facing genocide in Myanmar, currently has only two political representatives that have been allowed to stand in this year’s elections. In the app, their ethnicity is referred to as “Bengali” (a racist term that Burmese nationalists widely use for the Rohingya, implying they are immigrants from Bangladesh). After one of the only two candidates allowed to stand in the upcoming elections – Aye Win – publicly opposed the move, he was removed from the list of registered candidates and deprived of the right to political candidacy. Although several human rights organizations criticized the app, it has not been removed or the sensitive information deleted. A few news outlets, including Reuters, reported the removal of the app, however, at the time of writing (13 October), it was available for download for android smartphones and accessible online.

IDEA has publicly distanced itself from data management in the app – claiming it is the UEC’s responsibility. Head of International IDEA Markus Brand even openly attacked critics and accused them of spreading misinformation.

For a European observer, it is very embarrassing to observe the EU’s (financial) involvement in a racially intolerant and discriminatory project. The EU has traditionally driven the data protection agenda with respect to fundamental rights protection (take the GDPR for example) and acts as a privacy norm entrepreneur setting global standards that exert pressure for adaptation elsewhere. The above-described app project, however, constitutes a disregard of transparency and accountability that may potentially lead to an escalation in the 2020 elections.

With all those problems listed above – COVID-related and systemic – Myanmar does not need to add a newly-created one to its list that could actually be quite easily fixed. Time is ticking away, and the app is potentially incurring harm every single day of its online existence.

An abridged version of the article appeared in Myanmar Now.