Taiwan, as a non-United Nations (UN) member, is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention—key international treaty that defines who qualifies as a refugee, their rights, and the legal obligations of states to protect them. It also lacks a domestic refugee law. Consequently, individuals seeking protection—whether self-identified refugees or those already recognized by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR)—are processed on a case-by-case basis. This approach often results in inconsistent outcomes and places a significant burden on civil society organizations, which are left to provide essential support, such as accommodation, medical care, and psychological counseling, relying solely on their own resources.

This fragmented system is far from a systemic solution, underscoring the urgent need for comprehensive asylum legislation. Despite this, officials, including former President Tsai Ing-wen or former Premier Su Tseng-chang, maintain that existing regulations are sufficient. However, adopting an asylum law would mark a significant step toward aligning Taiwan’s legal framework with international human rights standards and demonstrating a commitment to protecting vulnerable populations. The government’s responsibility to act becomes undeniable in light of the reality: asylum seekers do exist in Taiwan (even though statistics are unavailable due to the absence of an asylum law and a corresponding monitoring system). Organizations such as the Taiwan Association for Human Rights (TAHR), Amnesty International Taiwan (AITW), and the non-governmental network supporting Hong Kong protesters facing potential riot charges have all called for the establishment of asylum legislation.

How is it that Taiwan—celebrated for progressive policies like same-sex marriage and high female representation in politics—still lacks such a law? While it might be tempting to attribute this to a lack of prioritization by the government and lawmakers, this explanation is overly simplistic and unhelpful. A deeper look reveals two significant barriers to progress. The first is the so-called “China factor,” which complicates Taiwan’s international and domestic policymaking, particularly in areas tied to sovereignty. The second is the assumption that public opinion would oppose such a law, further discouraging policymakers from pursuing the issue. Before addressing these barriers, it is important to examine the legislative processes related to asylum law that took place in Taiwan.

Past attempts to enact an asylum law

Efforts to enact an asylum law in Taiwan date back several years but have consistently stalled. The first draft law was introduced to Parliament in 2005. This proposal included provisions also for Chinese nationals—a point of contention that will be discussed later. Similar attempts were made in 2011 and 2012, with draft laws submitted and discussed in parliamentary public hearings. However, none of these drafts advanced to the parliamentary committee stage, a critical step in Taiwan’s legislative process.

Objections to these efforts often cited a lack of expertise to manage asylum issues and the absence of necessary supplementary laws to support the implementation of an asylum law. Compounding the challenge, Taiwan’s legislative process automatically removes all pending draft laws at the end of each parliamentary term. This means that with each new parliament, the issue must be reintroduced by key actors, such as parliamentarians, non-governmental organizations (as seen in 2005 when TAHR submitted a draft), or the government.

In 2016, during the new parliamentary term under the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), a record four asylum law draft versions were submitted. These drafts came from one Kuomintang (KMT) parliamentarian, two DPP parliamentarians—including Hsiao Bi-khim, now Vice President—and the Government. Notably, all versions excluded Chinese nationals. By this time, there was a consensus that this pragmatic approach would make it (politically) easier to pass an asylum law, leaving the issue of Chinese nationals to be addressed separately.

As the drafts in 2016 were quite similar, they were discussed simultaneously on the parliamentary floor under the supervision of the Committee of Internal Administration. The debates addressed numerous complex issues. Key discussions focused on how to define a refugee, whether individuals persecuted due to their sexual orientation should be included, and whether criminals should be automatically excluded. Other contentious topics included how to handle individuals who had been granted asylum elsewhere, those who had applied and been rejected previously, or asylum seekers who had transited through another country capable of granting asylum. Additionally, questions arose regarding the appropriate next steps if an asylum claim were rejected. Political considerations further complicated the discussions, such as deciding which government department would oversee asylum cases and how procedures would be implemented. Many governmental agencies expressed hesitation, reflecting a broader lack of consensus on key issues. Although the draft law successfully passed its first reading in the committee—a significant milestone in the legislative process—it ultimately failed to advance to the second and third readings due to unresolved disagreements.

At present, a new draft law has been submitted to the Parliament, but details remain scarce. Until now, the 2016 effort stands as the most successful attempt to date, coming closest to achieving legislative approval.

The China factor

As outlined above, Taiwan’s draft asylum law has been stalled in Parliament for several years, primarily due to the so-called “China Factor.” Taiwan’s complex relationship with China is inextricably tied to the debate on refugee policy. Recognizing asylum seekers as genuine refugees could, directly or indirectly, label their home country (or parts of it) as unsafe and persecutory. While geopolitical concerns and the implications of granting asylum for diplomatic relations are common for other countries too, for Taiwan this could turn out to be politically very problematic – especially in regards to China, but also in relation to Taiwan’s few remaining diplomatic allies (which actually have a record of human rights abuses) or the countries included in the Southbound policy (for example in Myanmar, the issue of the genocide of the Rohingya people is never mentioned by Taiwanese officials out of fear of offending a country Taiwan has been courting in the absence of diplomatic recognition for a long time).

As a matter of fact, the majority of asylum seekers in Taiwan come from China, Hong Kong, and Tibet. However, under the 1946 Republic of China (ROC) Constitution, still valid in Taiwan, these individuals are considered ROC citizens rather than foreigners. Furthermore, under the 1951 Refugee Convention, a refugee must have crossed an international border, but Taiwan still claims sovereignty over Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Tibet. Including these groups in an asylum law would therefore imply they are non-citizens, which could be seen as a de facto revision of Taiwan’s sovereignty claim. This raises the sensitive issue of Taiwan’s de jure independence—a topic China has warned could provoke military action.

In the past, the consensus was that passing an asylum law that excludes Chinese people from the People’s Republic of China might speed up the process (and the Mainland Affairs Council could then still amend the acts related to the Mainland Chinese and Hong Kong and Macao people to ensure the law is also applicable to them), but even such a version has not yet materialized. According to TAHR and AITW, all people regardless of nationality should be treated equally and these organizations see adopting a law excluding the Chinese as wrong. On the other hand,

South Korea provides an example of a country with a dual-system approach to processing asylum seekers. The system differentiates between ordinary foreign nationals (such as Syrians, Venezuelans, or Myanmar nationals, to name a few) and North Korean defectors. Notably, North Koreans are not classified as refugees. Instead, under the South Korean Constitution, which defines the country’s territory as encompassing the entire Korean Peninsula, North Koreans are granted citizenship following a vetting process. This is somewhat analogous to Taiwan’s constitution, which formally claims territories beyond its actual control.

Public perception of refugees

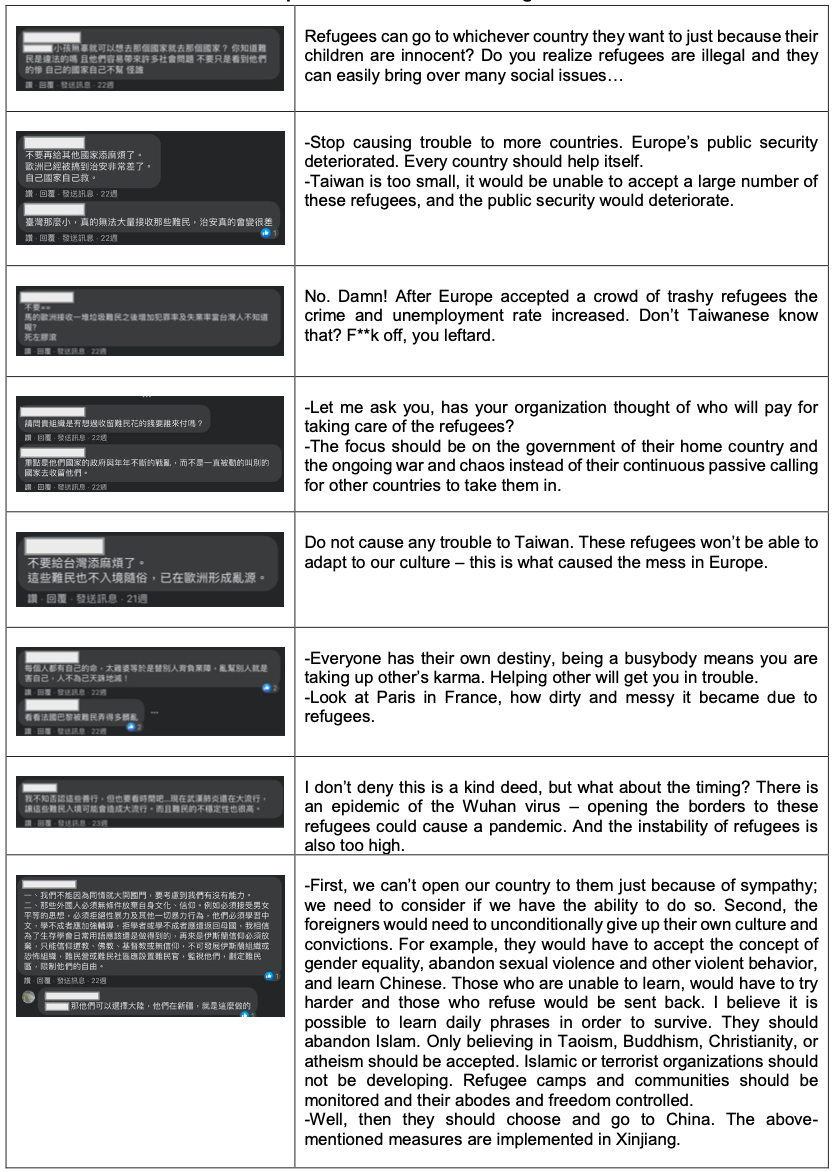

Another potential concern is the possible negative stance of the Taiwanese population toward an asylum law or the presence of refugees in the country. Social media platforms often feature harsh, and sometimes racist, comments that compare refugees to rapists and robbers, with Islamophobic remarks also prominently present (see Figure 1). This has led to a perception that Taiwanese people believe refugees would negatively impact society. However, as is often the case with social media, negative comments are more visible and prevalent than positive ones.

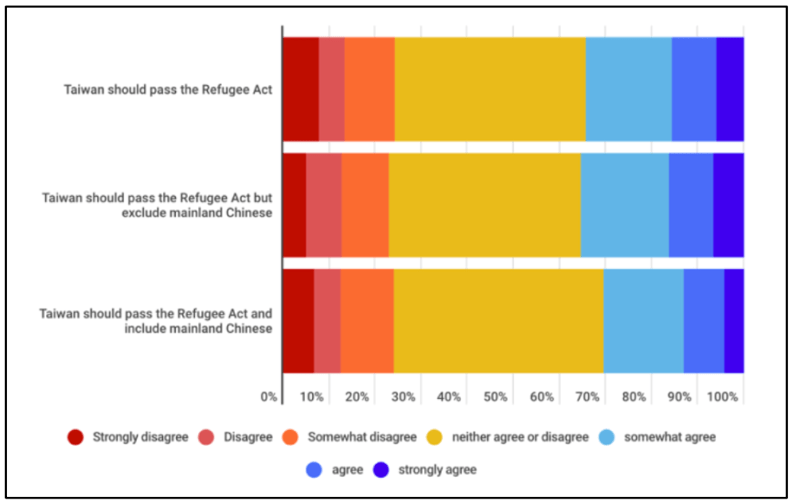

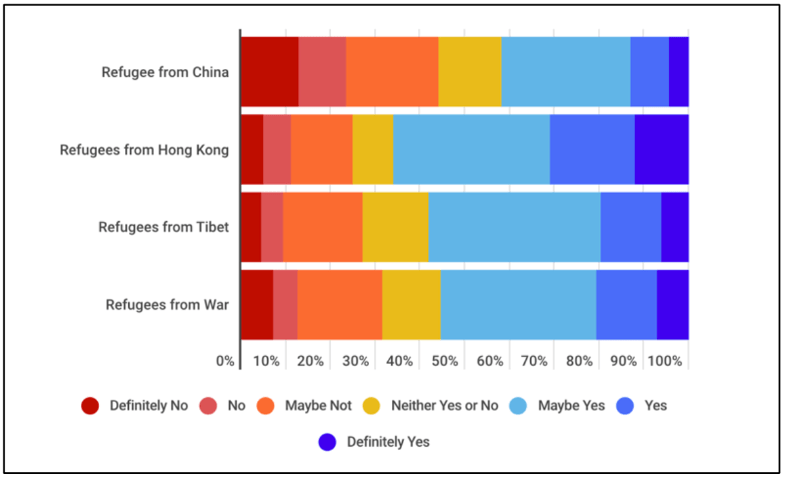

Research conducted by the author in 2022, based on a comprehensive, nationally representative survey (in terms of age, gender, and regional distribution), provides a contrasting perspective. While online forums may give the impression that Taiwanese society is largely opposed to granting asylum to refugees, the survey reveals that the Taiwanese population actually holds generally positive attitudes towards refugees and would be willing to accept them (see Figure 2) and tends to agree rather than disagree that Taiwan needs a proper asylum system (see Figure 3). However, a considerable portion of respondents remains undecided, underscoring the need for broader societal discussions on the topic.Top of Form

Figure 3: Taiwanese people’s opinion on adopting (different kinds) of an asylum law (Sinophone Borderlands Indo-Pacific Survey, 2022)

In conclusion, Taiwan’s lack of an asylum law reflects complex challenges, including the “China factor” and misconceptions about public opinion. Despite past efforts and recognition of the need for such legislation, progress remains stalled. Adopting an asylum law would not only align Taiwan with international human rights standards but also demonstrate its commitment to protecting vulnerable populations, reinforcing its image as a progressive and democratic society.

This article was produced as part of the project Human rights in East Asia (HUREA) funded by the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under the project No. 09I03-03-V04-00461.

The article was originally published by Taiwan Human Rights Hub.