Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting outflow of refugees has highlighted the need for Taiwan to adopt an asylum law.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has caused a huge wave of refugees, with over four million Ukrainians having already fled the country since February. The conflict has also triggered a wave of solidarity with the people of Ukraine across the globe. Taiwan has joined the ranks of supporters with (substantial) financial and medical aid, as well as announcements of easier access to visas for Ukrainians.

However, not to all of them. Only Ukrainian nationals that have relatives in Taiwan – who are either Taiwan nationals, Ukrainian alien residency (ARC) or permanent residency (APRC) holders – can now apply for a special visa to travel to Taiwan. This special visa is an entry permit for the purpose of visiting relatives and can be issued for a period of 30 days up to six months.

While it is admirable that Taiwan has reacted to a crisis so far from its shores, is the announcement of easier access to visas more a PR ploy than actual assistance?

The first question that arises is how many Ukrainian alien residence holders are there? Currently, there are only 49 APRC and 205 ARC holders from Ukraine in Taiwan including students, engineers, missionaries, and individuals working in various other sectors.

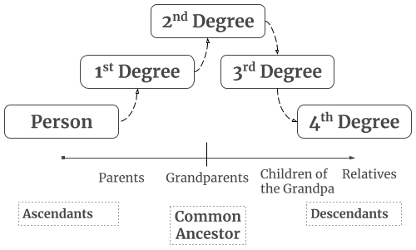

Second, what is the definition of a relative? Can, for example, a cousin apply? The announced visas are available for family members within 3 degrees of kinship. According to the Taiwanese civic code regulating this system, called qindeng (親等), the degree of relationship by blood between a person and his or her lineal relative by blood is be determined by counting the number of generations upwards or downwards from him or herself. In this system, one generation is considered as one degree of kinship (as illustrated in the graph below) and, because married couples are also counted as one, their spouse’s relatives are considered to be direct family. This means that while aunts and uncles of one’s spouse fall into this definition, one’s own cousins do not (they fall under the fourth degree of kinship).

Source: https://academia-lab.com/2016/06/16/kinship-in-roman-law/

The third issue is that applications must be made with a passport (original of photocopy) that is valid for another 6 months. Many people fleeing this war do not have the necessary documents and would not be able to apply. In Europe, on the other hand, Ukraine’s the neighbors have allowed all people, with or without documents, to pass the border into safety.

Due to these limitations, there are very few individuals who stand to benefit from the special visas for Ukrainians. So, while this announcement was a nice gesture, a more efficient and systematic plan is needed, one that establishes transparent rules for people seeking refuge and strengthens Taiwan’s human rights record.

Although debates on the issue occasionally have occurred in the past ten years, there has been no real progress. There was a draft asylum law in 2016 that passed the first reading in parliament, but did not progress any further. Recently, a new draft to the law was submitted; however, its contents have not yet been publicized, nor discussed in parliament. It seems there is not enough political will to push an asylum law through, as there are many lingering questions over the definition of a refugee and limits on numbers, as well as their rights and obligations. Nevertheless, adopting an asylum law is part of a broader push to bring Taiwan’s legal system in line with international human rights law.

In the absence of an asylum law that would regulate the entry of people from Ukraine, it is great to see initiatives by Taiwanese universities and educational institutions. Taiwan’s Academia Sinica and the Ministry of Science and Technology have launched a program offering 3-month scholarships to Ukrainian students and researchers (covering airline tickets, accommodation, and living expenses). Similarly, the Tunghai University in Taichung has announced full scholarships for degree programs for at least 10 Ukrainian students (covering tuition fees, living expenses, accommodation, and Mandarin language classes). These are, however, only temporary substitutes compared to what an asylum law could accomplish.

Whether Ukrainians would take up the option to flee to Taiwan is questionable, even if loser requirements were in place. Many people have chosen to wait out the danger in neighboring countries in order to return and rebuild their country as soon as possible. But while Taiwan is very far and may not be the first choice for many, they should, nevertheless, have this choice.

________________________________________________________________________

This article was originally published in the Taipei Times.