Richard  Q. Turcsanyi’s article published by the University of Nottingham’s IAPS.

Q. Turcsanyi’s article published by the University of Nottingham’s IAPS.

The Belt and Road Initiative (still commonly abbreviated as OBOR – One Belt, One Road) is undoubtedly one of the most ambitious international agendas of recent years and perhaps the most ambitious one ever presented by China. As such, much has been written and said about it, yet, obviously, many question marks remain. Lesser known, at least in the global context, is the Chinese initiative towards 16 Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, known as the ‘16+1’ platform. It is interesting to note that the two initiatives have some common features, as will be shown below. Moreover, since 16+1 was formed in 2011-2012 and its scope is not nearly as ambitious as OBOR, the first assessments of 16+1 can give some hints about how the OBOR might develop and what are the driving goals of Chinese policies towards these two diplomatic projects.

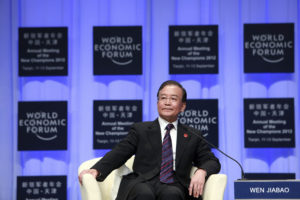

To start with, 16+1 came into being in a similar fashion as OBOR – step by step. In 2011, former Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao met 16 CEE economic ministers in Budapest and mentioned that China is willing to pay more attention in developing relations with this part of the world. The offer was repeated in a much stronger and more concrete form the year later in Warsaw, when Premier Wen presentedChina’s ‘12 points’ proposal to the CEE countries – which included, among other items, a US$10 billion credit line for projects in the region, planned increases of mutual trade, support for infrastructure projects, construction of industrial parks, and stronger political, economic, and social interactions to be coordinated by a new Secretariat at the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA). Finally, since the 2013 summit in Bucharest and already with Premier Li Keqiang in power, the 16+1 platform took a more institutionalized form with annual summits of premiers issuing guidelines as agreed upon at each meeting and reviewing the results the following year.

From this perspective, one may argue that OBOR has just experienced its Warsaw moment: after initial floating of the idea by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, the leaders of involved countries met in Beijing in 2017, a ‘Secretariat’ was created and bi-annual summits were announced, credit lines and other financial instruments are being offered, and promises of future trade opportunities are being heard.

Looking at the interests of the involved countries, CEE countries like their OBOR counterparts are interested primarily in the economics. They believe that China brings exciting new economic opportunities. Yet, politically speaking, they approach China at best with reservation and caution and at worst with outright security worries. These may be linked to direct geopolitical conflicts (in case of neighbouring countries of China), worries about economic domination of China (in most countries, but especially where Chinese presence reached relevant level), or even unspecified ideologically driven dislikes (especially in democratic countries). China is apparently fully aware of this situation and it frames the OBOR initiative as purely economic initiative and denies any (geo)political goals.

At this juncture, it is interesting to point out that when 16+1 was announced, similar discussion was going on with the Chinese side almost predominantly operating with economic goals as the drivers for the cooperation with the CEE. After five years, Chinese rhetoric somehow changed, shifting in favour of the highly developed political relations as the major achievement of the platform.

This can be seen to quite some extent as a reaction to real development. Politically, China-CEE relations have seen a major increase of diplomatic and people-to-people activity; it is a general consensus that China and CEE countries have never had such developed relations. Economically, however, the first five years of 16+1 has not lead to visible outcomes in terms of trade and/or investments.

When it comes to trade, overall CEE exports to China decreased slightly since 2012, while Chinese imports in CEE increased by similarly small margins. Moreover, there is no CEE country which has seen any relevant increase of trade, particularly exports to China, over the last five years. This is interesting especially given that CEE-China trade had grown quite rapidly in the comparable period before the establishment of 16+1 platform, but started to stagnate after the initiation of the platform.

In terms of investments, at most five Balkan non-EU CEE countries (which, however, comprise a relatively small share of the overall CEE economy) could suggest that they have seen increased economic activity. In terms of EU members, Romania, Poland and the Czech Republic are sometimes mentioned as countries experiencing rapid increase in Chinese FDI. However, the available statistical data does not confirm the rise and Chinese investments in all these countries are still negligible, forming at most 1-5 percent share of total investment stock in the country. (Most tend to fall even far below the 1 percent threshold.) Arguably, there are various projects being discussed and things may change in future, but as of now, the first five years of 16+1 platform can be described as ‘hot politics, cold economics’.

What the platform is clearly delivering, however, is a lot of ‘face’ for Chinese leaders in front of their domestic audience – and this is really where 16+1 and OBOR are pretty much about the same thing from Chinese perspective, although admittedly at a different level and size. Chinese leaders are presented to their people via active media reporting as highly respected by a large number of countries worldwide who look towards China with hopes for their future. China, on the other hand, comes and helps these countries in development, resulting in mutual gains, win-win situations, international peace, and so forth.

What I argue is that the main goals of China in both OBOR and 16+1 initiatives are political and linked to Chinese domestic politics, which really take the priority over the international politics for Chinese leaders. At the same time, accepting that the ‘core interest’ of the Chinese government is regime stability and that this stability relies upon the satisfaction of the populace and also smooth economic interaction with the outside world, OBOR and 16+1 are thus attempts to play with single move in both sides. The domestic population is satisfied when seeing China playing an important role internationally; the world is happy when China takes a cooperative rather than conflictual stance.

Obviously, politics and economics are closely interlinked everywhere, and even more so in China. Yet, in the case of the two initiatives discussed here, the economy should be seen as a means, not as a final goal. In this case, the two platforms are the cases of ‘politics by economic means.’ Since in 16+1 the economy has not yet really delivered its part(s), China has so far achieved its political goals by the promise of economic means.