Even though Singapore decriminalized consensual intercourse between men, the situation of LGBTQ communities is not so rosy across East Asia.

On November 29th, Singapore’s parliament decided to repeal a law banning homosexual sexual intercourse. This came after Singapore’s Prime Minister, Lee Hsien Loong, announced such a policy move back in August. While, on the surface, this was a significant move forward, the decision will merely help turn the everyday reality of gay Singaporeans into a legal one.

The origin of Singapore’s law banning homosexual sex, however, helps us better understand the colonial history of East Asian countries and the significant differences in approaches to LGBTQ rights across the continent. Meanwhile, Taiwan’s recent legalization of same-sex marriage seems to show a possible path forward.

Singapore is continuing on an already-set path

If taken out of context, the fact that Singapore repealed the law criminalising sex between men seems like a significant step forward for LGBTQ rights. However, the controversial law 377A has not been enforced in recent years, allowing the local LGBTQ scene to flourish and establish itself through places such as gay nightclubs or yearly parades, which were only interrupted by the pandemic. What made the repeal quite bittersweet for many was an amendment to the city-state’s constitution, passed around the same time, which upholds the ‘traditional’ definition of marriage as being between a man and a woman. This move was also previously announced by PM Lee back in August. He promised to ensure that the concept of ‘marriage’ as one between a man and a woman is going to be better protected by the government.

This ‘one step forward, but not more’ approach towards equal rights is, however, a continuation of the government’s previous stance. Following a discussion on repealing the law in 2007, the government explicitly promised not to enforce the controversial law but to still keep it on the books to appease both sides. Furthermore, earlier this year, Singapore’s Court of Appeals ruled the law unenforceable, setting the stage for the announcement in August. Thus, the move follows a precedent under which the city-state’s government does not take leaps on social issues but, instead, just treads (somewhat) forward.

The colonial history of Asia’s anti-LGBT laws

Singapore’s ‘anti-gay’ law dates back almost 100 years, originating during British colonial rule. With many Asian countries being former British colonies, it is no wonder that traces of this colonial past remain in their legal codes and, thus, also influence social and legal attitudes towards the recognition and rights of LGBTQ people. The 377A is an example of the most significant piece of the former British colonial legislation regarding what now are LGBTQ rights. It traces its origin to section 377 of the Indian Penal Code from the year 1860, which criminalised “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” and was used to criminalize same-sex sexual activity (mostly between men). Serving as an example of a proper colonial penal code, similar laws were implemented in other colonies of the British empire. In Asia, after gaining their independence, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore, and Myanmar inherited the penal code and, alongside it, Section 377. A similar postcolonial ‘hereditary’ nature of anti-LGBTQ laws can be seen in Central Asia’s ex-USSR republics. The reality was, however, different in former French colonies. Because sodomy was decriminalized in post-revolutionary France, its protectorates had no such laws. Thus, former French colonies in Asia, such as Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, have never criminalized same-sex sexual relations, which did not change even after their independence. In 2022, Vietnam has furthermore officially moved away from pathologizing homosexuality.

Notably, various countries and cultures across Asia can be said to have historically had a much different and even more open approach toward different forms and natures of sexuality than the generally Christian West with its perception of sodomy. For example, homosexual relationships in pre-Meiji Japan were perceived to be on a level similar to heterosexual ones. In Han China, bisexuality was quite normal. In pre-colonial Hinduist India, the Hijra, a gender beyond the ‘traditional’ male/female binary, had a significant cultural and religious role and, thus, were respected appropriately.

Therefore, the introduction of anti-gay laws in many East, South and Southeast Asian countries can often be attributed to the impact of the former colonial power on the colony’s laws. It often did not reflect the particular cultures and histories of the individual countries or the sometimes invoked conservatism of the ‘Asian values’. Even countries which were not colonies, such as Meiji-era Japan or Siam, were influenced in the late 19th and 20th centuries by the modernization coming from the West. Thus, they adopted and appropriated the Western legal systems, introducing anti-gay laws.

The current-day reality of LGBTQ rights in Asia

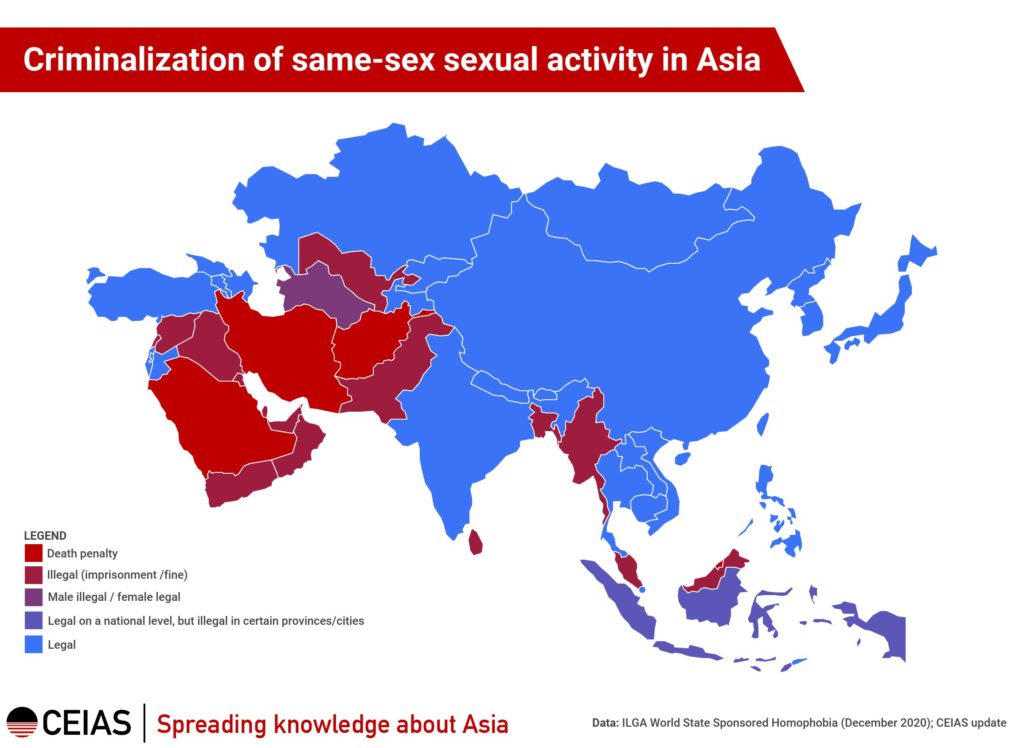

As the previous cases show, the differences in the historical experience of various countries directly impacted the laws and social attitudes towards the treatment of LGBTQ people. Moreover, with such a vast continent and such a vast range of experiences as was present in Asia, and still is to this day, countries approached the topic of equal rights differently. The differences are apparent, ranging from absurdities such as death penalties for same-sex sexual activity in hard-line religious Islamic countries, such as Iran, Saudi Arabia or Afghanistan, to the recent liberalization of same-sex couples’ right to marry in Taiwan. Different cultures, historical experiences or religions can wildly shape social and legal attitudes towards sexuality.

According to the 2020 State-Sponsored Homophobia report of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA), there were 21 UN Member States in Asia where same-sex sexual intercourse was explicitly criminalized and one (Iraq) with de facto criminalization. Since then, with legalization in early 2021 in Bhutan and the passage of legislation in Singapore, the numbers have dropped to 19 plus 1. In direct continuation of the colonial legacy of the Indian penal code, Section 377 is still a part of the legal code in countries, such as Bangladesh, Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. While the level of its enforcement varies, it is still being actively used to persecute people. India, where Section 377 originated, has been relatively progressive when it comes to equal rights, however. In 2018, the country’s Supreme Court scrapped Section 377, with the Chief Justice of India, Dipak Misra, going as far as proclaiming that “Any consensual sexual relationship between two consenting adults – homosexuals, heterosexuals or lesbians – cannot be said to be unconstitutional”.

However, the case of state-level legality does not give a complete picture of gay and, more broadly, LGBTQ rights. Such is, for example, the case of Indonesia, where, while legal on a national level, several provinces have laws penalising same-sex intercourse. The most infamous in this way is probably the Indonesian province of Aceh (with its hard-line Islamic criminal law), where there have been cases of public caning as a form of punishment, amongst other ‘offenses’. Indonesia’s recent move to make sex outside of marriage punishable by jail also effectively criminalizes same-sex relations due to the illegality of same-sex marriage there. Implementing such laws thus serves to create not only an (often religious) norm for heterosexual but also non-heterosexual relationships.

Furthermore, besides legality, there is also the realm of social and public acceptance and the overall norm-setting associated with sexuality. As mentioned, attitudes towards same-sex relations in China’s history were generally more open. It was only during the Qing dynasty that homosexual acts were outlawed. In 1912, with the country’s turn to a republic, it was ‘re-legalized’. Thus, in current-day Taiwan, homosexuality was never really outlawed, although it was societally pathologised for a certain period (in the 1950s). On the other hand, the mainland People’s Republic of China (de facto) reintroduced the criminalization of male same-sex sexual activity between 1979 and 1997 under the pretence of ‘hooliganism’. After a certain period of ‘respite’, the LGBTQ community in China has been again facing increasing pressure in recent years. LGBTQ-related issues are often treated as results of ‘Western’ influence and, thus, denigrated by nationalists. State institutions also often regulate and censor content in media which showcases same-sex relations, and as of late, norms of masculinity are being policed as well. Further issues in China include the still-existent conversion therapies, into which many LGBTQ people are pushed by pressures from their family and close friends.

Same-sex marriages are still banned across most of Asia, with only Taiwan legalizing them in 2019. Other forms of partnership are only respected in Cyprus, and foreign marriages are recognised in Israel. Taiwan’s legalization of same-sex marriages happened following a 2-year deadline set by the Supreme Court, which ruled on the unconstitutionality of their ban back in 2017. The court’s ruling required the legislature to pass a law allowing same-sex marriages; otherwise, they would become legal automatically, as was, in the end, the case. Seemingly a great leap forward, caveats, including restrictions on adoptions, still apply. While Taiwan was the first in Asia, proposals, possible court cases, and small changes across sub-national governments may help push for broader acceptance of same-sex marriages. An example of such a first step could be the recent decision of the Tokyo metropolitan government, which adopted legislation recognising same-sex partnerships, extending to same-sex couples living in partnership some rights applying to married heterosexual couples. In India, the Supreme Court also recently decided to accept a petition seeking the legalization of gay marriages, which may kick-start the process of legalization there. Furthermore, in Japan, the Tokyo District Court in November 2022 recognised that the country’s lack of a legal system for same-sex couples to become family members presents a “grave threat and obstacle” to people’s humanity.

Other things to note that differ from country to country, culture to culture, and religion to religion are laws and restrictions related to gender identity and the ability to change one’s legal gender. For example, in India, transgender or nonbinary people have the right to change their gender identity enshrined in the constitution and have their rights protected by law. Alongside this, a third gender option, related mainly to the Hijra, also exists. A similar reality can be seen in Bangladesh.In Nepal, people are allowed to change their gender to a ‘third gender’ – effectively breaking the ‘traditional’ binary.

Incidentally, in Iran, where homosexuality is punishable by death, people are allowed to change their gender, and gender reassignment surgeries have been subsidised by law since the fatwa in 1986. By declaring gender-confirmation surgery and hormone-replacement therapy religiously acceptable medical procedures, the Islamic theocracy, in theory, acknowledged that someone’s sex assigned at birth might differ from their gender. A thing to note is that while these laws may exist, trans and non-binary people across Asia (and the world) still face discrimination from the larger society and the government and are often still required to undergo sex-reassignment surgery along with a complicated and humiliating process to change their legal gender.

Legacy of colonialism and human rights

In his work Orientalism, Edward Said points out the crucial connection between perceived sexuality, sex and Orientalism. It was the “exotic” oriental sexuality that was seen as “threatening” the colonial power’s morals. With the colonial powers and their Orientalist discourse playing a deciding role in how the “exotic” colonies were governed, it is no wonder the impacts of 19th-century decisions and views on sexuality are visible in the laws governing the lives of LGBTQ people and communities across the postcolonial world. With Singapore taking a step to repeal Section 377A, we see another part of the colonial legacy in Asia disappear.

However, with other issues beyond simple legality still present, equality is still far away. Many countries still punish gay people for having sex, sometimes even with the death penalty. Trans people are still facing discrimination and are unable to live the lives they deserve.

Furthermore, while these few examples have been brought up in this article, there are numerous other issues worldwide, such as the legality of conversion therapies or a lack of healthcare access for trans people (amongst many others), which directly hurt LGBTQ people. And while the different histories, cultures and religions of various countries have contributed to different ways people look at sex, sexuality or gender, one thing should be sure. Human rights should pertain to everyone equally, regardless of nationality, sexuality, gender identity or anything else.