China has never been really at the top of the political agenda in Slovakia. The interests of the ruling SMER — Social Democracy party, which was in power from 2006 until March 2020 besides a short interval in 2010–2012, began th development of trade interactions with China, often forgetting about security or human rights issues.

However, 2020 has so far seen a changing policy towards China on the part of the Slovak government. The change has been motivated by two main factors.

Firstly, the 29th February general elections resulted in the Social Democrats losing their grip on power. The new government was formed by a wide coalition of mostly right-ofcenter parties, which tend to have a more value-based view of China, putting more focus on human rights and protecting democracy from China’s influence. Due to this change, we have recently seen numerous government politicians calling on China to release Panchen Lama, the second-highest-ranking monk in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition and a political prisoner since the age of six, allowing Taiwan to participate in the World Health Assembly, and condemning Beijing’s attempt to unilaterally impose security legislation on Hong Kong.

Secondly, Slovakia, like virtually every other country, had to deal with the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought about a newfound interest in China, its internal politics, and international ambitions.

These developments however did not occur in a vacuum, without any reaction from China. On the contrary, they were unveiled against the backdrop of Chinese propaganda spreading in Slovakia. Moreover, it appears that the pandemic was a major factor in the Chinese Embassy changing its approach to pro-Chinese propaganda in Slovakia.

Back to the future: The Embassy joins social media

After years of a notable absence on social media, China started using both Facebook and Twitter accounts in February 2020. This activity fits within the broader trend of Chinese diplomats getting on “Western” social media in order to fulfill Xi Jinping’s directive to “tell the China story well”.

As both social media accounts were registered only in February, they do not have a large following yet, which limits their potential impact on the Slovak public. Nevertheless, China’s approach to social media showcases the general trends in which the country’s approach towards communicating with foreign audiences has recently been going.

Interestingly, almost 40 percent of the Embassy’s followers on Twitter created their accounts in 2020, which suggests that there is a large number of bots following the account. At the same time, a large portion of followers are the accounts of other Chinese embassies and diplomats.

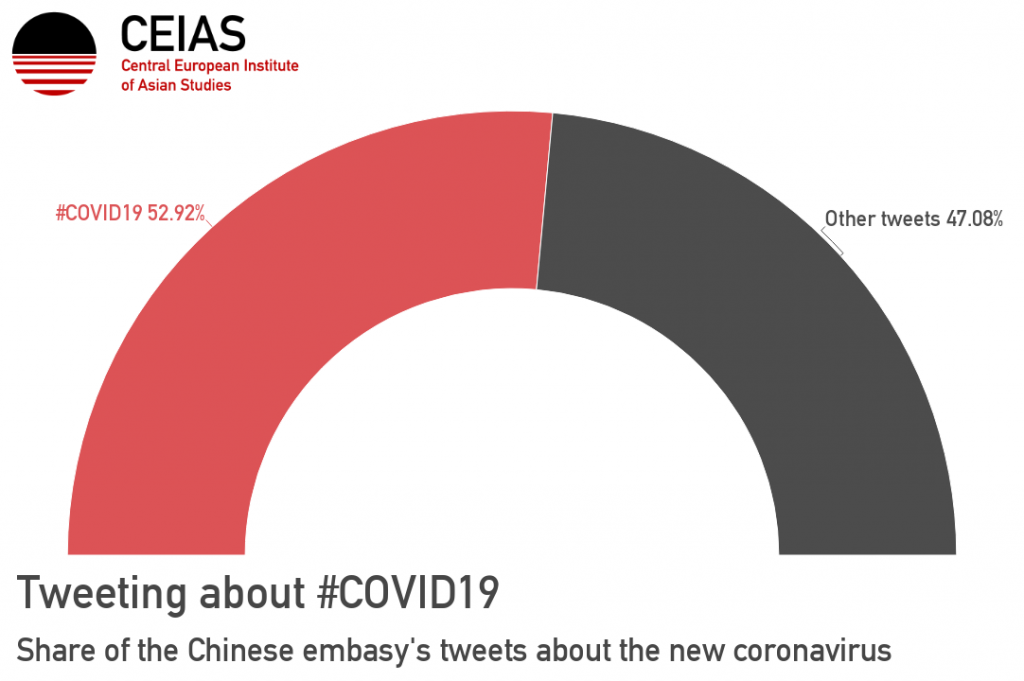

Naturally, the Embassy has dedicated a majority of its focus to the COVID-19 pandemic. More than half of the tweets posted since the account was opened in February 2020 included the hashtag #COVID19 in some variation.

However, many of the tweets are of poor quality as they appear to be a result of automated translation of Chinese or English language source materials, which miss the nuances of Slovak which translates some English terms in more than one way, thereby resulting in a different meaning than the original.

#RumorBreaking

As various actors of the Slovak security community (both state actors and NGOs) started to engage in strategic communication about the pandemic and China’s role in the breakout, the Chinese Embassy launched a campaign aimed at breaking purported rumors about China and the pandemic. So far, 13 infographics were published on Facebook and Twitter which “debunk” the purported myths about the origin of the virus, expediency, and transparency of China’s response to the outbreak, Taiwan’s response to the virus, and its influence over the WHO. Overall, these “infographics” can be characterized as a mix of truth-bending, misinformation and creative semantics. This was a part of a larger coordinated campaign targeting more countries, as similar infographics and articles were posted by Chinese embassies in Berlin, Warsaw and Athens. An article on 24 myths was published by the Chinese news agency, Xinhua.

Interestingly, the campaign which was originally supposed to contain 16 “broken myths” ended at 13. This was most likely due to quite strong backlash accusations from the Slovak public on the Embassy’s Facebook page. The “truth” of these “myths” was in all cases purported to be based on either unspecified scientists or rationality, even in cases where the original “myth” was not connected to any question of science, such as the question of Taiwan’s accession to the WHO or the fate of Dr. Li Wenliang, a doctor from Wuhan who first noted cases of a SARS-like pneumonia and was later reprimanded by the police for “spreading rumors”.

Slovak media: finding internal resilience?

Besides engaging on social media, the Chinese Embassy has relied on more traditional approaches to spread propaganda and disinformation on the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the past, China relied on local Slovak proxies in the media industry and in politics.

In the past, the Chinese Embassy used the Trend magazine to spread China’s view of the world to the Slovak public. In 2019, the embassy purchased ad space which was used to publish a propaganda-riden advertorial aboutthe Hong Kong protests. The advertorial was met with stern criticism from fellow journalists. The embassy was set on using space in Trend again in 2020. The magazine was supposedly approached by the embassy, which wanted to purchase ad space to publish another advertorial on the COVID-19 pandemic and China’s successful response to the outbreak. Unlike in 2019, this time the magazine’s editors opposed the request, as the ad purportedly contained grossly misleading and false claims.

Facing rejection from the mainstream media, the Embassy had to resort to using fringe media outlets. In May 2020, the Slovak National Newspaper published an interview with Sun Lijie, the Chinese Ambassador. The interview largely focused on the positive presentation of Chinese mask diplomacy. While the media outlet in question is in and of itself a marginal one, it has a symbolic value. The newspaper and its online version are published by Matica Slovenská, a publically financed cultural and scientific institution. It’s history goes back to the 19th century when it was originally founded by leaders of the National Revival movement.

Local proxies prove their worth

Still, the most effective way for the Chinese embassy to get its message on the pandemic across, included neither the abuse of Slovak media nor the Embassy’s social media presence. The biggest reach of the propaganda came by getting local political proxies to spread Chinese talking points. This has been recognised in the past as one of China’s key tools to influence foreign perception of China.

The most notorious China proxy in Slovakia is Ľuboš Blaha, an MP for the social democrats and a self-proclaimed Marxist, who is known for regularly engaging in virulent anti-EU and anti-NATO rhetoric.

Blaha’s Facebook posts (here and here) about China’s mask diplomacy, in which he juxtaposed supplies of masks and other protective equipment from China with the purported lack of aid from the EU and America. Blaha regularly described the supplies as “aid” even though a substantial majority of the supplies were of a commercial nature.

He also peddled the idea that there is a possibility that the virus originated in the USA and was deployed against China as a biological weapon.

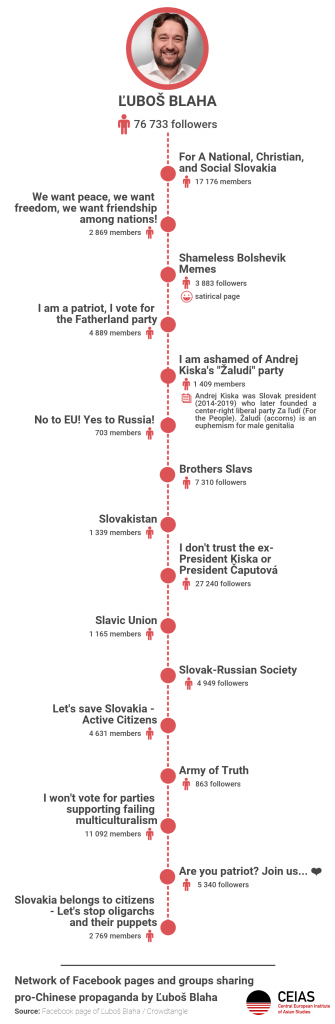

Unlike the Embassy’s own social media posts, propaganda and disinformation posted by Blaha had a wide reach. The post about the possible origin of the virus in the USA was liked by 2.8 thousand people and shared 970 times — a high amount by Slovak standards. Moreover the post was shared also by pages promoting neo-nazi content, pro-Russian propaganda, and anti-liberal messages. Together, they boasted over 5,000 interactions and almost 100,000 followers.

One of the posts on “Chinese aid”, titled “When all the bad Communists are suddenly helping Europe,” was even more successful — it was liked 5.5 thousand times and shared 1.8 thousand times. Through a network of like-minded Facebook pages and groups (collectively boasting almost 140,000 followers) that shared the post, 8.5 thousand people interacted with it.

The list of Facebook pages and groups demonstrates growing alignment between pro-Chinese and pro-Russian channels for spreading disinformation and propaganda. Growing synergies between the two countries hybrid warfare tactics in Europe is a trend that has been accelerating in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has sent the Chinese Embassy in Slovakia into propaganda overdrive. Besides relying on traditional tools for spreading propaganda, the Embassy started using relatively new tools as well. However, the newly established social media accounts are not yet reaching their full potential. Due to their recent establishment, the Facebook and Twitter accounts currently have a low amount of followers. Nevertheless, we can estimate that social media will play a more pivotal role in China’s communication strategy in Slovakia soon. This seems to be the trend elsewhere in the world, with some of China’s social media “wolf warriors” even securing promotions, thereby reinforcing the trend.

As a result, hybrid threats, misinformation, and propaganda posed by China will play an increasingly important role in Slovakia’s security environment. Is Slovakia ready for this development? Time will tell.

The article originally appeared on the Digital Communication Network blog as part of the series of publications on Digital Challenges in the Time of COVID-19 Crisis.